KEY POINTS

- Republicans chafed at a $600 weekly increase to unemployment benefits in the CARES Act.

- The enhancement paid numerous workers more money than their prior incomes. Some lawmakers thought it would avoid employees from going back to work and keep back the recovery.

- A $900 billion Covid relief costs, which uses a $300 weekly benefit boost, likewise takes “return to work” rules for states.

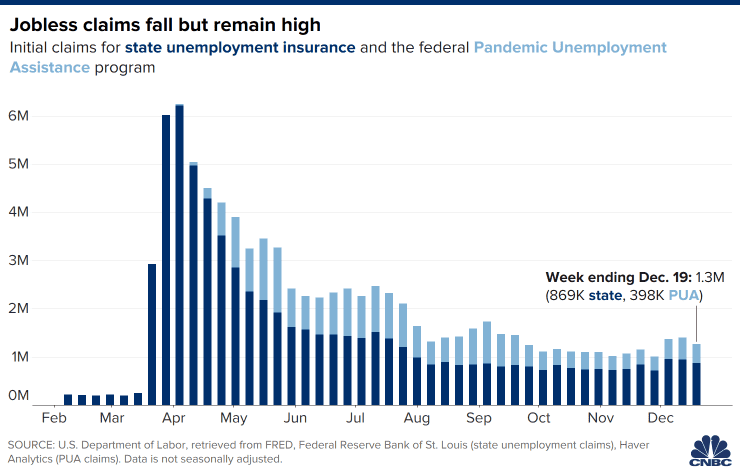

A familiar tug-of-war around work and boosted joblessness benefits has reappeared as jobless workers appear poised to get a $ 300 increase in weekly advantages.

Workers would get a $ 300-a-week infusion through the middle of March as part of a $900 billion Covid relief expense package awaiting President Donald Trump’s signature.

Tucked into the bill are “go back to work” rules for states, which should make sure companies have a way to rat on employees who deny a task deal. Such a rejection renders employees disqualified for unemployed advantages– and the additional pay.

The guidelines mostly total up to pageantry, given that they don’t produce a new legal requirement for workers, and states already have mechanisms in place for such reporting, according to labor experts.

More from Personal Financing: Millions will lose unemployed advantages in days as Covid relief costs await limboThe relief Americans could lose if Trump vetoes stimulus package void relief expense permits bigger cash rollovers for reliant care

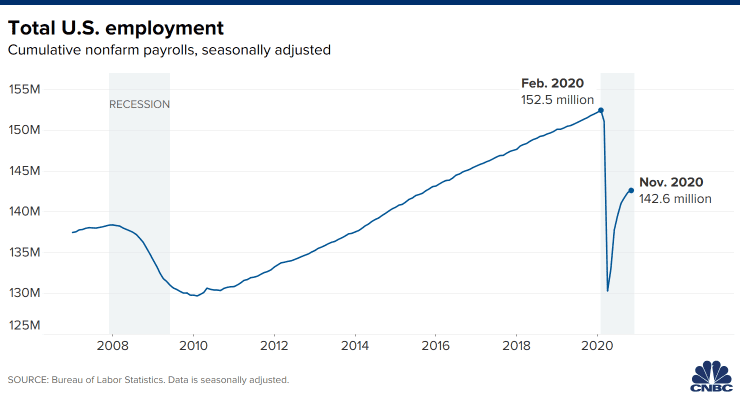

Nevertheless, the rules restore a heated argument from the early days of the Covid pandemic and its resulting economic catastrophe. At the time, lots of Republicans thought generous advantages offered an incentive to stay unemployed.

“I’m not amazed,” said Michele Evermore, a senior policy analyst at the National Employment Law Job. “It’s been a substantial talking point all year.”

$600 a week

When Congress provided a $600-a-week boost to unemployment benefits in the spring, as part of the CARES Act, the reaction was swift and intense.

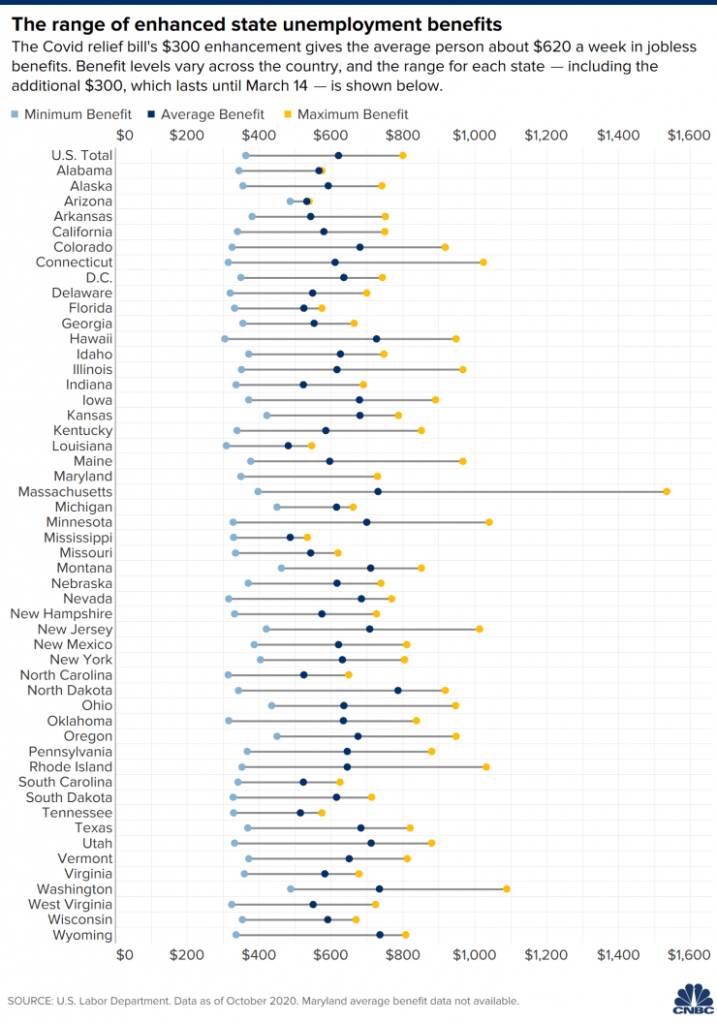

The goal of the infusion, coupled with normal state benefits, was to fully replace lost incomes for the average worker– almost $1,000 a week. (Normal state benefits generally change half of the lost earnings.)

But lots of employees, mostly those with lower pay, made more while out of work than at work.

Lots of conservative legislators berated the policy as a disincentive to go back to work. Such a dynamic would hold back the economy from a quick rebound, they argued.

Democrats argued the improvement was a need. Millions depend on the earnings support to pay costs and put food on the table, at a time when discovering a task was tough and it made good sense to keep people home to prevent spreading out the coronavirus, they stated.

Many studies discovered the $600 stipend didn’t have a negative effect on the labor market. In the aggregate, it didn’t prevent individuals from trying to find work or trigger them to leave a task, they discovered. Organizations didn’t have difficulty hiring for task openings.

“There weren’t enough jobs and too numerous individuals were out of work,” stated Ioana Marinescu, an assistant professor of economics at the University of Pennsylvania, who co-authored one of the studies. “It just wasn’t a problem on the huge scale of things.”

Tug of war reappears

The supplement lapsed in July. Democrats wished to extend it however Republicans were opposed.

This time around, legislators appear to be less vocal about their opposition, but the relief legislation shows it’s still on their minds, according to labor professionals.

“It’s leftover from the $600 issue,” according to Andrew Stettner, a senior fellow at the Century Foundation, a progressive think tank.” [The legislation] is trying to make all states be more vocal on this concern.”

A $300 cash infusion might have a bigger disincentive impact now, given labor-market improvements from the height of the crisis, Marinescu said. But it’s not a significant issue, she said, since there’s still a scarcity of tasks and the economy hasn’t rebounded to the degree it would present a hazard.

“It’s simply not all that bad, and we need the stimulus,” she stated.

Plus, fewer employees would exceed complete wage replacement with a $300 increase, which is half the level of the CARES Act subsidy and the exact same amount as a Lost Income Assistance program developed by President Donald Trump over the summer season.

The normal individual would replace about 85% of their pre-playoff income with an additional $300, according to an analysis by Ernie Tedeschi, an economist at Evercore and a former Treasury Department official.